Activity

-

Anna Talley posted an articleBeyond the Algorithm: Research Workshop Comparing Human and AI Problem-Solving. see more

Introduction

With artificial intelligence’s promise of universal solutions, we are at risk of losing the cultural significance of our problem-solving muscle–especially because reliance on generative AI would maintain and prioritize Anglo-American perspectives and technological frameworks. In the race for artificial intelligence advancement, our research examines the tensions between human and generative AI creativity, and we ask many questions about capabilities, limitations, and inherent biases of this technology. This article presents our study thus far with a specific focus on our workshop conducted with the Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group (SIG) of the Design Research Society (DRS). The research project mentioned in this article is titled Anotherism, and the research workshop was conducted as part of this investigation.

Framing

In 2016, it took Tay, a chatbot developed by Microsoft and launched on Twitter, less than twenty-four hours to turn into a racist and sexist entity—demonstrating how the data it learned and trained on was and is biased (Vincent, 2016). However, Tay's predecessor, XiaoIce, released in China in 2014, served very differently. Designed as an AI companion, XiaoIce focused on creating long-term relationships and emotional connections with its users, while Tay was made to gain a better conversational understanding at the expense of… (Zhou et al., 2020). Eight years later, the challenges with artificial intelligence are the same: bias. The common thread between AI chatbots and generative AI is the fact that they learn from data created and generated by humans on the internet. So, what led to Tay becoming racist and sexist, is contributing bias in image generation. With different image-generation tools available to those interested in 2024, generative AI faces more challenges than the problems it may solve. After analyzing 5,000 images, Nicoletti & Bass (2023) learned that images constructed with the generative AI tool Stable Diffusion amplified gender and racial stereotypes. This research demonstrates that, like early AI chat bots, generative AI carries the potential for inaccuracy and misleading outputs, data fabrication, and can present hallucinations confidence (Nicoletti & Bass, 2023).

As women of color from the Global South, we are deeply concerned about the inherent Anglo-American bias in generative AI. This bias is evident in generative AI's design and intended use, primarily within an Anglo-American context. One of our ongoing explorations is to understand whether these biases are embedded within the data AI learns from or if they emerge due to choices made in the development process. Broadly, we posit that AI enables technological colonialism by imposing solutions and mindsets developed in the Global North onto the Global South rather than utilizing or facilitating local or regional practices and innovations. As a result, in this project, we ask: How might an AI solution devoid of local context impose a monolithic approach to problem-solving regardless of regional cultures, practices, and behaviors?

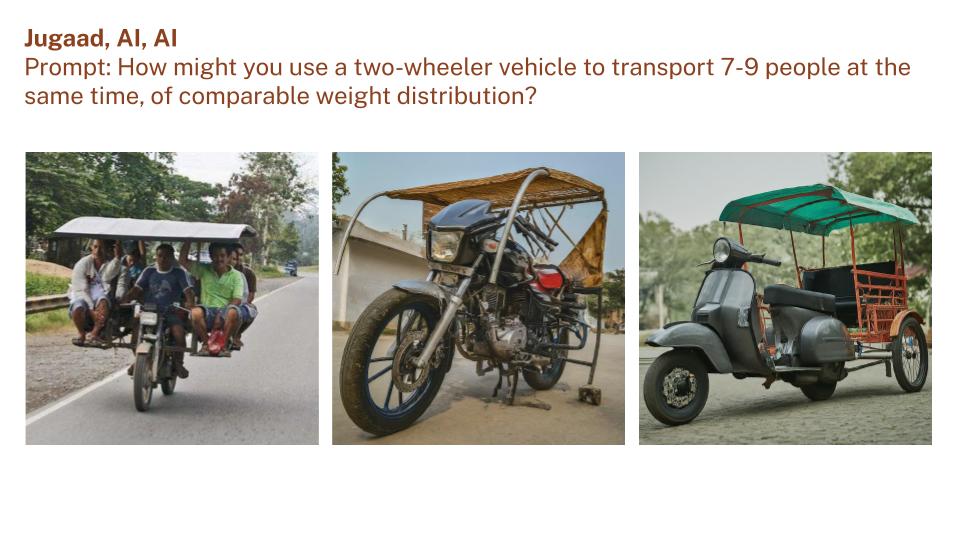

The foundation of AI is biased, but as design practitioners who use and develop these tools, we need a better understanding of generative AI’s limitations to effectively utilize it as a tool. Through our research, Anotherism, we compare Jugaad with generative AI to unpack how and where the biases appear. Drawing on the concept of jugaad— Hindi for an improvised solution based on ingenuity, cleverness, workaround and innovative problem-solving—a practice that transcends the Anglo-American context, we are critically evaluating the risks of generative AI solutions not rooted in local contexts. Dr. Butoliya (2022) describes the jugaad as an act of freedom, a bottom-up reaction to the top-down oppression caused by the capitalist subjugation of the market and societies (Butoliya, 2022). For Indians like us, jugaad demonstrates joy within restrictions, where scarcity leads to innovation. However, much of the imagery of jugaad on the internet limits its ingenuity, resourcefulness, and humanity. Thus, Anotherism uses jugaad as a critical mode of reflection while tracing the gaps in the learning models and recognizing the biases of AI-generated content.

Human Ingenuity vs AI Generations

Our work started by developing and learning from generative AI with no expectations[1]. We started exploring the fact that a computer is—of course—not a human, and recognized that we need to learn how humans solve problems to truly compare the differences and similarities between humans and generative technology. This research workshop and project defined humans as social beings with complex experiences and a capacity for abstract thinking. Humans have a wide range of emotions and connections; in this project, participants are from different parts of the world with a diversity of perspectives and identities. Generative technology, though complex, is not as complex as humans we are interacting in our research workshops—human complexity is not a recruitment criteria, instead an observation. With this project, we are starting to explore and define the gap between humans and generative AI to define how design practitioners can utilize generative AI to support their ingenuity and problem-solving. In order to learn about human ingenuity, we collaborated with the Pluriversal Design SIG to offer a research workshop. In this workshop, we were set to explore the same prompts and generations we explored with ChatGPT, Gemini, MidJourney, Claude, and other tools.

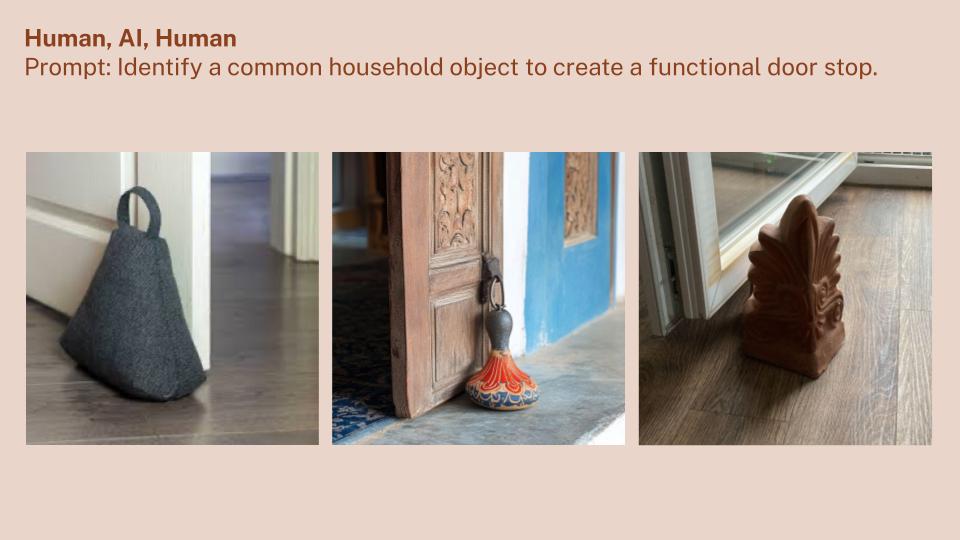

Image Caption: Generative AI responses to doorstops in an Indian Households

Generating with Humans: Workshop Findings

For the Pluriversal Design SIG workshop, we prompted the workshop participants to identify a common household object with which to create a functional door stop so that we could study:

- What context, knowledge, and lived experience do humans use to address everyday problems?

- How does the solution resonate with the cultural context in which it lives?

- How practical are the solutions we generated together?

From a ball of socks, a rope, wooden wedges, and folded paper, the workshop participants came up with all sorts of things and truly expanded our facilitators' understanding of "doorstops." Before the workshop, we hypothesized that humans think about the physical, chemical, and gravitational characteristics of objects before creating a solution. However, being in different parts of the world can make a difference because the context for each participant would be different in that case. Ahead of the session, we asked the participants to tell us more about themselves so that we could understand the varied backgrounds and experiences they brought to the workshop. From our survey, we learned that 57% of the participants identified as white, 28.6% were Asian, and 14.3% were Latino/Hispanic. While most respondents knew what jugaad meant, only 80% were likely to fix things around the house or address everyday problems.

The workshop participants generated diverse solutions. However, the discussion about their motivation was more significant for our research. Most of the participants relied on repurposing existing materials and evaluated the practicality of an object while reflecting on the social norms and meanings attached to the object being repurposed. While describing their solution, one of the participants said, "the element was… an acroterion and it's a traditional Greek roofing element… But now I use it to keep the door open. Suddenly, from being just beautiful. Now it has a function."

Similarly, one of the participants shared an image of an iron-cast piggy bank of a Black Americana, which the family used as a doorstop before moving to the United States. However, because of the cultural tension and conversation about race, the participant and their family decided to not use it as a doorstop anymore. Here, we see social norms and context changing the purpose of an object and its usage. For others, this problem-solving exercise was about intuition. One of the groups prototyped in real-time and used socks as a doorstop. While the human prototype worked perfectly, this is one of the solutions that we're unable to recreate—at this point—using generative AI. The conversation during the workshop naturally gravitated toward buying versus creating because human ingenuity and problem-solving are nothing if we are buying everything around us rather than rethinking our household and everyday problems.

Implications

Our central hypothesis and project pillars are that humans draw their understanding of the immediate environment, needs, and limitations, leading them to highly adaptable and feasible outcomes. Solutions that represent balanced imagination with constraints of physics and practicality, focusing on function. Human problem-solving often includes cultural adaptability, empathy, and emotional intelligence— qualities that generative AI currently lacks. Meanwhile, generative AI solutions often defy the laws of physics, prioritizing creative and imaginative outputs over practicality. Turns out, it's the age-old debate of form versus function.

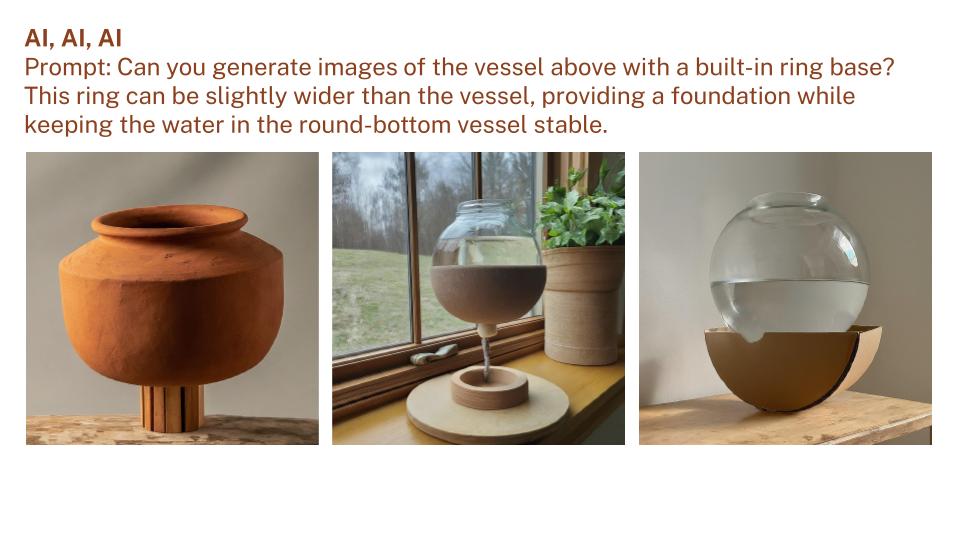

After studying several generative AI process maps and creating images, we believe that generative AI currently adds a country layer to its renders and outputs. As we experiment with different text and image-based AI tools, the words jugaad and India result in much different imagery than grassroots innovation, adhocism, or kanju—practices similar to jugaad. During the workshop, this assumption turned into an insight, as we heard one of the participants share how they use sandbags as a doorstop, and we realized that when asked, MidJourney added patterns and designs associated with Indian aesthetics on a sandbag. Is that an issue, you might ask. We believe it is because, in this instant, problem-solving to generative AI meant reinforcing and prioritizing Global North perspectives, regardless of where the solution is intended. At this time, generative AI is not effectively integrating diverse local knowledge and practices to decenter Anglo-American narratives, but the bigger question is, will it ever?

We are continuing to explore generative AI tools and human problem-solving and hosting a roundtable discussion on November 15, 2024. We will also be conducting another virtual workshop in early 2025. Contact us on the following email if you are interested in participating: anotherismproject@gmail.com.

[1] Prompts used to generate a lamp using jugaad:

- Create an image of a household item being used as a lamp, using the principles of jugaad in an Indian household

- Create an image of a household item being used as a lamp with a lightbulb or other electrical features, using the principles of jugaad in an Indian household.

- Using the principles of jugaad in an Indian household, create an image of a household item being used as a lamp with a lightbulb or other electrical features. Make this lamp hang from a wall or the ceiling, and it should be large enough to light up a 150 sq foot room

- Using the principles of jugaad in an Indian household, create an image of a household item being used as a lamp with a lightbulb or other electrical features. Make this lamp hang from a wall or the ceiling, and it should be large enough to light up a 350 sq foot room in an urban Indian city

- Using the principles of jugaad in an Indian household, create an image of a household item being used as a lamp with a lightbulb or other electrical features. Make this lamp hang from a wall or the ceiling, and it should be large enough to light up a 350 sq foot room

-

Anna Talley posted an articleFull proceedings from the PIVOT 2020 and PIVOT 2021 conferences are now available! see more

We recently uploaded the full proceedings from the PIVOT 2020 and PIVOT 2021 conferences to the DRS Digital Library. To learn more about these events, the role of the DRS' Pluriversal Special Interest Group and what you can find in the Digital Library, please find below a conversation between Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel (NCSU) and Dr. Renata Leitão (Cornell University/OCAD University), co-convenors of the Pluriversal Design SIG and founders of the PIVOT virtual conferences. Lesley-Ann chaired the 2020 edition, and Renata chaired PIVOT 2021.

How is the Pluriversal SIG involved in the conference?

Renata: As convenors of the Pluriversal Design SIG, we wanted to create and facilitate pluralistic conversations about design and bring together people from all over the world who share similar values.

Lesley: We (PluriSIG) created the Pivot conferences to make sure we had a space to focus on conversations around shifting centers, methods, epistemologies, and ontologies. We wanted to focus on a different point of view and examine these through a lens of decoloniality, but moving beyond just an academic critical perspective to a creative and generative one.

What is the Pivot conference?

Renata: Pivot emerged as our small contribution to change the culture of the international research community. It was born from our observation that many designers of color and from peripheral countries were not part of the main narrative of design. We would like to know what these designers are doing and creating outside the center. We thought that we had to bring to the center stage more diverse voices, from different places, with different accents, perspectives, and ways of understanding the world and practicing design. So together we could talk about changing the world.

Lesley-Ann: We also were very aware from our own conference experiences that designers from outside the center, such as designers from the Global South and designers of color, often ask very different research questions due to their different worldviews. Therefore Pivot would be a space where these conversations and discussions would happen and where what is perceived as the dominant epistemologies in design would not be privileged. It would be a space for many epistemologies and ontologies, as well as many forms of participation.

How did it begin and who was involved? What is your role?

Lesley-Ann: Pivot 2020 interestingly started with an obscure budget line that I could have access to that was available for ‘conversations about design’ by prominent speakers! That budget line sparked discussions between myself (Lesley-Ann Noel, Tulane University at the time), Laura Murphy (Tulane University), and Renata Leitao (OCAD at that time) about redefining who could be considered ‘prominent speakers’ in design. Renata and I had already formed the SIG when I joined Tulane University. Laura had a history of supporting writing through weekly and monthly writing retreats and was interested in my conversations about decolonizing design, power, and hegemony.

We named the conference Pivot in late 2019 and were thinking of the pivot in point of view away from hegemony. We started to design Pivot 2020 as an in-person unconference and writing retreat. People would come with work-in-progress and then finish the work after their presentation in collaboration with people they had met at the conference and with writing support from the Pivot conference chairs and the writing facilities available at Tulane University.

New Orleans was supposed to be the venue for this in-person event. New Orleans itself is on the fringe, straddling both Global North and the Global South. So even the location informed the way we started to plan the event. We thought New Orleans was the ideal place to discuss decolonization, multiple epistemologies, diversity, and issues that might seem peripheral to the main narrative of design.

We were planning this event to create an environment for collaboration and to be sure that people we wanted to hear from weren’t intimidated by the academic process. We had to pivot (like the whole world) in March 2020 when the pandemic became ‘official.’ So the name became even more relevant. We took the same level of care in creating a virtual experience where people could really connect with others. We (me, Renata, and Laura, the conference chairs) worked with the rest of the Pivot 2020 core team —Maria de Mater O’Neill, Michele Washington, Maille Faughnan, and Samantha Fleurinor— to make sure people could feel welcome and could feel heard in the one-day virtual event in June 2020. Interestingly, we never used any money from the budget line that sparked the conversations. Pivot 2020 was a very horizontal event with no ‘prominent’ speakers, but with a great diversity of presenters and stories from Indonesia, India, Kenya, Brazil, the Caribbean, Australia, Uruguay, Japan, Canada, several European countries, the Middle East, and the United States, and more.

Renata: Pivot 2021 emerged from the wish to write another call for papers. Since June 2020, conversations around decolonizing design, diversity, decoloniality, and pluriversality have started to get more traction. Often, when ideas become popular, there is the danger of becoming bland and shallow. People were questioning how to put those ideas of decoloniality and pluriversality into practice. Pivot 2021 was born from the desire to frame the conversations in a more tangible manner. Organizing a new conference was the chance to write a call for papers to invite people to consider the tools we designers create to reshape our world. And also to consider that dismantling and reassembling are complementary movements of change. So I wrote a first version of the CFP and shared it with Lesley-Ann and a few friends who brought many suggestions. They joined the adventure as members of the organizing committee (Laura Murphy, Michele Washington, Maria de Mater O’Neill, Pawel Pokutycki, Maria Rogal, Sucharita Beniwal, Manuela Taboada, and Nicholas Torretta). At the same time, I was talking with my colleague from OCAD University, prof. Immony Men, about designing new ways to share information and new formats for virtual conferences. He joined us as a co-chair and, as an expert in interaction design, helped develop the format and create a smooth experience.

I was the chair and main organizer. I had the chance to work with a brilliant team of graphic designers and digital artists from OCAD. I had the invaluable assistance of Jananda Lima in managing the conference. She also created the conference’s visual identity.

Jananda, Immony, and I chose the people who inspired us the most in recent years to give keynote talks (and inspire our participants). We had the criteria to choose people who represented different parts of the world and identities. We were blessed to receive Dori Tunstall, Bayo Akomolafe, Dany Pen, Casei Mecija, Jason E. Lewis, Cash Ahenakew, Sharon Stein, and Arturo Escobar. Please go to our website and watch the recordings of the keynote sessions. Each one of them brought something special.

What are the conference’s main aims and structure?

Lesley: In Pivot 2020, the main aim was to get people writing, talking, and sharing their creative and regenerative ways of decolonizing design. Since Pivot 2020 started with the unconference and writing retreat format, it involved a lot of coaxing and coaching to get to the thirty-six presentations and papers. In addition to the usual peer review, Pivot 2020 included one-on-one support for authors. In some cases, student assistants downloaded the transcripts from presentations and helped the authors organize them into written text. The review committee provided lots of feedback on the drafts. We gave guidelines on producing the presentations and gave people tips on presenting on the day. You could say that “Access and participation” were keywords for 2020, in addition to the conference theme of “designing a world of many centers” since these concepts are also key to decolonizing design.

Renata: We all have spent our lives on Zoom since 2020. In organizing a virtual conference, we wanted to create an experience more similar to a real-life conference. The social aspect is very important: having informal conversations with people and having fun. The organizing committee brainstormed different formats. In the end, we decided to use two platforms: Zoom, for the keynote presentations and parallel panels, and SpatialChat, for the informal conversations. Between the presentations, we go to the SpatialChat to socialize. One of our graphic designers, Dorsa Kartalaei, created beautiful virtual environments on SpatialChat. Everybody was captivated by the Green Room. At lunchtime (Toronto time), we had musical presentations. Nicholas Torreta played on the first day and Juliane Gamboa & Léo Brum on the second. We had so much fun on the second day, “dancing” on SpatialChat. We even had conga lines! Nothing bonds people as much as having fun together.

Can you provide a brief summary of the themes in the 2020 and 2021 conferences? Did you see a change? What remained the same?

Lesley: In 2020, the big themes were sharing practices, decolonizing design education, unlearning hegemony. The host institution had a social innovation focus. Several of the contributions reflected that due to how the call was shared. Most of the contributions were case studies as people were eager to share that the Pluriverse already existed and that we were already living in a world of many centers.

Renata: In 2021, the big themes were “Repairing and Repurposing as Design,” “Other Ways to Relate,” “Narratives Between Multiple Worlds,” and “Learning with the South.” We had much more papers about AI and exploring the more-than-human. We also had a strong focus on political design. I think the papers in 2021 were much more focused on questioning tools and practices than in 2020. What remained the same was the participation of people worldwide, bringing many different perspectives.

Do you have any highlights from the proceedings (individual papers, etc.) uploaded to the Digital Library that are “must reads” for researchers and/or doctoral students?

Lesley: From Pivot 2020, it is worth reading or watching Maria Rogal’s reflective short paper on the Wixárika Calendar where she shares lessons learned as western design and Indigenous epistemologies collide. Because it’s a method paper, Susan Wyche’s short paper, which was created from the transcript of her presentation, on cultural probes is another must-read. When I think of PIVOT 2020 highlights, many are videos, which are still available on Tulane’s website. Some of the video presentations were very powerful. I recall how everyone was speechless after Omari Souza’s presentation about racism in design. Lucia Trias and Arvind Lodaya, who are both independent researchers, also gave presentations that were very well-received. Lucia is critical of the evolution of design in Uruguay, while Arvind examines the tension between design and craft in India. Both are addressing the ‘acculturation/deculturation’ that happens as design education moves to different countries. Arvind is more direct when he talks about binaries between modern and primitive that happen in design discourse.

Renata: From Pivot 2021, my favorite papers are the “Calendar Collective” by Kalyani Tupkary, “Being Co-conspirators” by Mudita Pasari and Prachi Joshi, “Story-making” by Jane Turner and Manuela Taboada, and “Approaching Ubuntu in Education Through Bottom-Up Decolonisation” by Seehawer, Ngcoza, Nhaze, and Nuntsu. I want to highlight the tremendous participation of the Design & Oppression network from Brazil. They submitted four papers (from Bibiana Serpa, Sâmia Batista, Fred van Amstel, Rodrigo Gonzatto, and others).

Where else might people turn if they want to learn more about some of the themes and issues that have been discussed at the conferences?

Renata: Visit our website (pivot2021conference.com) and watch the recording of our sessions. You could also join the PluriSIG and participate in our book club.

Lesley: The Pivot 2020 papers are in the DRS archive of course, and the videos are available as a playlist on youtube. We continue the discussions in our monthly Pluriversal Design Book Club, where we discuss the work of authors from outside of what might be considered the mainstream of design, so authors from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean; and BIPOC authors.

Do you have plans for a Pivot 2022?

Renata: No, no plans. Maybe 2023.

Lesley: No. There won’t be a Pivot 2022. We had started conversations with a few people about moving Pivot outside of North America, but perhaps everybody needs some time to recover from the craziness of the last two years. If people or organizations would like to be involved in a future Pivot, they should reach out to us.

What role has the DRS played in the conference series?

Renata: DRS gave us a lot of guidance and institutional support, particularly for the first one, Pivot 2020. This year we were more experienced, but we know that we can count on DRS’s staff.

Lesley: Yes, The DRS was very helpful by sharing the typical conference timeline and the proposal structures, including budget templates, that would normally be used for the DRS and LearnXDesign conferences. We also got a lot of support in archiving the papers.

What do you see as the benefits of having the proceedings uploaded to the Digital Library?

Renata: It is important to make this content accessible and retrievable by anyone.

Lesley: What she said :). I’m really happy that we were able to make even oral presentations retrievable by giving the transcripts doi numbers. In this way, hopefully, we’ve been able to play a role in expanding how academic work is documented.

-

Isabel Prochner posted an articleGet involved with Global Health SIG, Pluriversal Design SIG and Design Pedagogy SIG see more

DRS SIG News: CFPs, Meetups and More

DRS SIGs have been busy planning and hosting events, despite this unusual and rather chaotic academic year. There are lots of ways to engage with Global Health SIG (GHSIG), Pluriversal Design SIG (PluriSIG) and Design Pedagogy SIG (PedSIG) and participate in design research activities.

GHSIG has been developing a crowdsourced repository of COVID-19 Public Health messages and information set by official national, regional and international bodies. This will be a source of information that researchers, public health authorities and policy makers can access and forward to communities around the world. The team is also analysing the data for a multinational and multicultural visual and language communication analysis of COVID-19 public health messages. They've started the analysis and expect to develop guidelines and a white paper on best practices. You can view the repository here.

GHSIG also has a call for abstracts for a Little book on Global Health: Special Edition on COVID-19. They’re looking for proposals for short case studies on health and wellbeing—the deadline is coming soon on 15th October. The book will be published in 2021 and will also include outcomes from the GHSIG Conversation at DRS2020.

As for PluriSIG, they’ve been running a bimonthly book club that reviewed and discussed Escobar’s Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy and the Making of Worlds and Santos’ Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide in September. The selections for October are Pluriverse: A Post-development Dictionary (16 Oct) and Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30 Oct). Visit Eventbrite to view the schedule or register.

Finally, PedSIG has been buzzing with activities including bimonthly Distance Design Education Meetups and a discussion on the Futures of Design Education planned for 29 October. PedSIG is also organising their next biennial conference Learn X Design 2021, which will be hosted by Shandong University of Art & Design in September 2021. Full paper, workshop and case study submissions are due in March.

Check out the DRS Events Calendar for a list of more design research events and add your event by contacting editor@designresearchsociety.org

The DRS is also looking to expand the SIG program. Contact admin@designresearchsociety.org to learn more.

-

Isabel Prochner posted an articlePivot 2020 aimed to generate learning and conversations around the Pluriverse see more

Conference Report: Pivot 2020

Pivot 2020 invited participants to consider how to design a ‘world of many centers and voices.’ We asked questions like: What does a world in which many worlds fit look like? What is needed to create this reality? Who is needed to support this change? Pivot 2020 aimed to highlight diverse voices, perspectives, epistemologies, and ontologies with an emphasis on design and social innovation.

The event was initially planned as an in-person conference in New Orleans, USA. This location felt appropriate given the city’s diversity, history, and proximity to the Caribbean, Latin America and ‘other worlds.’ Then COVID-19 arrived and forced us to change our plans and adapt to an online format. We worked through the disruption and uncertainty of the pandemic and invited people to join us for a day of virtual conversations. We always wanted to host a more inclusive conference and the online format helped us achieve this goal! It allowed for greater diversity of participants: we had presenters and stories from many countries—e.g., Indonesia, India, Kenya, Brazil, the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand, Uruguay, Japan, Canada, several European countries, the Middle East, and the United States.

Above: Screen shot of participants from across the world

The event took place on 4th June 2020 on Zoom. We had a full day of presentations and discussions—8 sessions and more than 40 presenters stretched over 11 hours. Since we chose not to have parallel sessions, everyone watched the presentations together and engaged in conversations. The sessions covered themes such as ‘the Pluriverse is now,’ ‘decolonizing design education,’ ‘unlearning hegemony,’ ‘digital and emerging tech,’ ‘decentering futures,’ and more.

There was significant debate among the presenters and audience about the need to create epistemologies and methods for design theory, practice and education that can help design move away from its traditional Eurocentric approach and move toward more plural forms of participation. Conference attendees proposed new courses for a pluriversal design education, challenged each other to diversify their references, and shared suggestions for a more diverse reference list. These ideas and discussions will be made available through the Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group.

One of our biggest challenges when planning the event was to simulate a conference atmosphere. In our view, the social and interpersonal aspect at conferences is almost as important as the presentations—it enables new connections, meaningful encounters between people thinking along the same lines, and the formation of a community with shared interests. To support this social aspect, we divided Pivot 2020 participants into occasional breakout rooms to chat and meet each other. We also had a very active chat-box where some of the most meaningful connections were formed. We were positively surprised by the level of engagement in these chat-box discussions!

Many of the presenters sent us pre-recorded video presentations. These videos are available on the DRS YouTube channel and the Taylor Center’s webpage, enabling further post-conference engagement. Pivot 2020 conference proceedings will be published later this year.

Authors

Dr. Renata M. Leitão, Conference Co-chair and Pluriversal Design SIG Convenor; Instructor, OCAD University

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, Conference Co-chair and Pluriversal Design SIG Convenor; Associate Director for Design Thinking for Social Impact, Phyllis M. Taylor Center for Social Innovation & Design Thinking, Tulane University

-

Isabel Prochner posted an articleIs 'Design so White' in Emerging Critical Design Studies? see more

Reflection on Keynote Debate 3: Whose Design?

As a follow-up to DRS2018, we invited select conference participants to reflect on the Keynote Debates and related conversations that took place during the conference. The article that follows responds to debate 3 - "Whose Design?: Sharing Counter Perspectives on Dominant Design Gazes." It was prepared by Renata M. Leitão (OCAD University) and Lesley-Ann Noel (Stanford University), track chairs of "Not Just from the Centre - Multiple Voices in Design" at DRS2018.

Whose Design? Is 'Design so White' in Emerging Critical Design Studies?

Throughout the DRS2018 keynote debates, a huge screen behind the speakers and the moderator showed questions asked by the audience, allowing for a certain participation in the debate. And still, the most asked question was not addressed for two days: “why is design so white?” As co-chairs of the track "Not Just from the Centre — Multiple Voices in Design," this question is central to our work. Not that we believe that design is itself white – as the practice of world-making, it is ubiquitous and widespread –, but mainstream narratives of what constitute “good and valid” design excludes non-Eurocentric perspectives.

Even if that hot question was not addressed for two days, we could see a clear change in the demographics and interests of DRS delegates, compared to previous conferences. The rooms of critical tracks – such as "Designing for Transitions" and "Design, Research and Feminism(s)" – were completely crowded, contrasting with the empty rooms of a few more mainstream tracks. Critical conversations ranged from "A Feminine Approach to Design" to "Indigeneity and Mestizaje in Latin America." Around us, many discussions between delegates involved encouraging the participation of designers from the global South in DRS conferences. Indeed, we both played a part in the process of encouraging more designers of color to participate when we proposed our track.

The question “why is design so white?” was addressed in the third Keynote Debate “Whose Design?: Sharing Counter Perspectives on Dominant Design Gazes” by Andrea Botero (moderator), Sadie Red Wing and Arturo Escobar. Dr Botero asked an important question: "for who is design so white?" Because from her perspective as a Latin American scholar who collaborates with other critical design scholars, design does not seem that white. Inspiring presentations from Indigenous designer Sadie Red Wing and from Prof. Arturo Escobar unveiled counter perspectives. Escobar argued that a field of transnational critical design studies is currently emerging. After three days of encouraging conversations about countering Anglo/Eurocentrism and oppressive perspectives in design among DRS delegates, we have to agree with Escobar.

But still, developing transnational critical studies in design has some challenges. It is noticeable that the question “why is design so white?” was only addressed in the keynote debate between two Colombian academics and an Indigenous academic. The participants of the first two Keynote Debates where not able to address the most asked question. Are only non-Anglo/Eurocentric designers capable or expected to address this kind of question? We hope not, as this question is relevant for the role of design in building and transforming our world and its social structures. Could white design scholars unlearn design Eurocentrism? Could North American and European designers learn from different perspectives and be able to constructively participate in the transformation of design research and practice? We have to believe the answer is a “yes.” And the promising conversations among DRS delegates need to be transformed into actions and new structures that allow for the unlearning of Eurocentrism in design.

Escobar has asked how we can develop non-Eurocentric design work (Escobar, 2018). Design conferences are not known for being diverse spaces. It is not unusual to go to a design conference and count the people of color on one hand. Therefore, one of the first steps to answering this question would be to ensure that these spaces are more diverse. This DRS conference was inspiring because it was evidently more diverse and conversations about diversity were loud. The organisers even managed to facilitate distance participation of several presenters including Adolphe Yemtim from Burkina Faso and Octaviyanti Wahyurini from Indonesia. If we want to talk about diversity, multiple voices in design and constructing a non-European design imagination, we have to address the systemic challenges and barriers that make participation of designers from outside ‘The Centre’ so difficult. Both Yemtim and Wahyurini, among other presenters, faced visa challenges. Another participant withdrew his paper when he considered the cost of participation compared to his cost of living. The hegemony of the English language in design research also creates another barrier to participation. The conversations and participation at the DRS2018 were inspiring, but the challenges faced also remind us that so much more needs to be done.

Authors

Renata M. Leitão, OCAD University

Lesley-Ann Noel, Stanford University

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

-

Isabel Prochner posted an articleRadical, liberatory, intercultural and pluralistic conversations about design see more

Introducing the Pluriversal Design SIG

We’re thrilled to announce a new DRS Special Interest Group (SIG) — Pluriversal Design (PluriSIG). The group promotes radical, liberatory, intercultural and pluralistic conversations about design. PluriSIG is convened by Lesley-Ann Noel and Renata M. Leitao, and includes organising committee members Tanveer Ahmed, Xaviera Sanchez de la Barquera Estrada and Nicholas Baroncelli Torretta.

Read more about this group and their mission on the PluriSIG page, and contact the convenors to get involved!

The group has already initiated a discussion on the meaning of Pluriversal Design. Noel and Leitao have also announced upcoming projects for the group:

- PluriSIG Book Club

- Weekly group readings of relevance to the SIG, followed by discussions on the SIG discussion page. The first book is Design for the Pluriverse by Arturo Escobar. Other authors on the reading list include Mario Blaser, Isabelle Stengers and Boaventura de Souza Santos.

- Decolonizing Design Reference Lists

- This project will co-create design reference lists including authors from a variety of cultures and countries.

- Pluriversal Design Resource Library

- This project aims to collect and share resources that promote pluriversality, such as anti-oppression tool-kits, guidelines for community engagement, anti-design saviorism toolkits etc.

- Discussions and Interviews

- Vimeo channel with curated interviews about design practices, epistemologies and design research methods that challenge concepts of modernity and development, and highlight the work of design researchers from outside Europe and North America.

- Celeste Martin likes this.

- PluriSIG Book Club